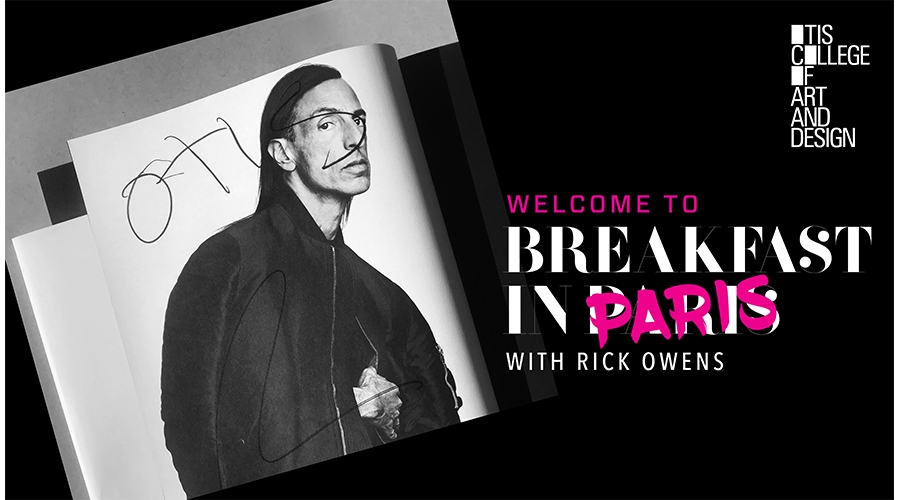

In the past year, few fashion designers have spoken to the moment as eloquently and honestly as Rick Owens. The Paris-based designer grew up in Porterville, in California’s San Joaquin Valley, in a household that prioritized books and reading over television, where memories of the pageantry and mystery of going to Catholic mass still impact his work. “That was my first taste of exoticism. All of these dragging robes, these gray dusty temples—it was exotic and glamorous, but also connected to morality,” he said to Clarissa M. Esguerra, Associate Curator of Costume and Textiles at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, as part of a virtual conversation on March 25 organized by Otis College’s Board of Governors and new co-chairs Patricia Röckenwagner and Todd Goldstein. During the hour-long virtual event, Owens discussed his upbringing, his work, and how the past year of pandemic lockdowns and a social climate marked by intolerance and bigotry has impacted his recent collections.

For his latest, the Fall/Winter 2021 women’s collection, which was shown on March 4, Owens and his small, five-person team organized a show in Venice’s Lido, not far from the atelier in Concordia, Italy where his clothes are designed and made. It was an all-hands-on-deck affair. “How do you do a show during a pandemic? You do it without an audience and a reduced crew,” Owens said. “I decided to show it in our backyard. We didn’t import teams of hair and makeup people. We were doing hair and makeup. We were doing the dressing, and taking the pictures. Then we had this fantastic backdrop.”

The show has been described as “cinematic, otherworldly, and superheroic” by Vogue, and it begins with models walking down a long path atop one of the beach’s many breakwaters, a plume of white smoke trailing in the background. A drone camera captures the models overhead as they walk the length of the makeshift runway, and then a different camera swoops over to the “backstage” area where Owens and his tiny team are helping the models change into new looks. It’s a rare sight to see the designer behind the scenes.

Titled “Gethsemane”—a reference to the garden in Jerusalem where Jesus went to pray the night before his crucifixion—the collection features hourglass gowns, jackets with oversized shoulders, sequined jumpsuits, and long, puffer capes. “What are we collectively experiencing right now? We’re experiencing dread, we’re experiencing threat,” Owens said. “But when you’re thinking about mortality, you start thinking about what your real values are, and I’ve always been interested in somehow connecting values to fashion and clothes.”

“Your show gave me a feeling of validating my fears, but that it’s going to be OK, too,” said Esguerra. “The exaggerated shapes, the shoulders—seeing it in this context made me think of armor. The puffer pieces were comfort. The body pieces that were hanging from the waist were like shedding skin, shedding a layer. Am I reading into it too much?”

“In the eighties, that kind of shoulder was about an emerging womens liberation and gay liberation,” responded Owens. “There was a superhero element that spoke to people. Looking at it now, I’m thinking that it’s not the time to speak to those needs. It’s not about power, it’s about defiance. It’s about defying intolerance and bigotry. And, also, it’s about how we’re living through a difficult moment, and to step up and do our very best.”

Owens said that after showing these collections during the pandemic he and his team have a new energy: “I’ve always worked in such an isolated way. Once the factory [in Italy] opened up and I could go back after the lockdown, I said, ‘This is where I need to be.’” After the double threats to health and the economy, Owens felt that staying in Italy more and rallying the troops was essential.

“It’s intimacy, but also survival,” he said. “It was a moment of threat and now there’s a new sense of gratitude that we survived that, so there’s a feeling we want to be stronger.” As for showing up more in the footage of his recent shows, Owens asked, “Does it sound pompous to say I wanted to be the captain of the ship and show my face and be there for the group?”

Owens said that because the fashion calendar has become so unrelenting, the industry has a prescience that perhaps has eluded the art world. “When I look at fashion, I think of it as communication,” he said. “To be a designer you have to say something that people are interested in listening to, and you have to do it constantly and you have to maintain a level of interest and relevance that is different from art now. There’s something about that conversation that is, I don’t know, more compelling than art. Maybe fashion is more important than art. Is art fashion? Art is very much about fashion and status and the transcendent moment. I’m just saying that with fashion, we’re doing it faster and more often.”

You can view Owens’s “Gethsemane” runway show here.